Major props to Carole Ann for recommending Museum Speelklok (the music box museum) in Utrecht. It was probably the best museum I saw on my trip, and I saw a lot of museums – thanks to the Museumkaart for making this fiscally practical. This place combined (obviously) music (including the Charleston), history, simple machines (most of which were human-powered), programming, particular Dutchness, and a tour guide who encouraged swing dancing. I visited this fine establishment on my third trip to Utrecht (a.k.a. “cutrecht“), and it made the entire trip worthwhile.

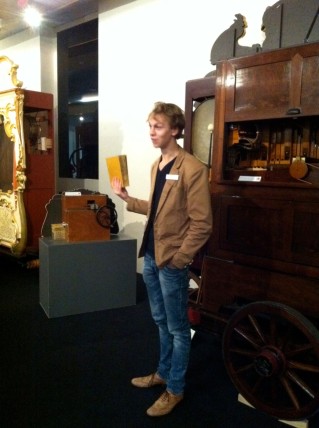

The last guided tour of the day was underway when I arrived, and I joined it, which turned out to be a good decision because normally, visitors aren’t allowed to play any of the music machines, but the tour guide demonstrated several of them (he even let us take turns playing one!). I learned that there are three basic music-making mechanisms for the music boxes: Bells, steel combs, and air (usually through pipes, but also, there is air used to move a mechanism to strike a percussion instrument). I think the steel combs became popular later in the history because they were cheap and easy to manufacture (requiring only a single cut piece of steel for the comb and a cylinder with raised dots to pluck the comb).

Most of the instruments he showed were quite elaborate in their appearance as well as their sound. A mechanical bird in a cage sang while opening its mouth and turning its head from side to side. The singing used air blown through small pipes. Both the singing and the motion were quite realistic – it was really a brilliant design choice since the motion of a bird turning its head is so naturally mechanical with the quick turns and pauses. Also, there was a hat that I think played using a steel comb, and at a point near the end of the song, a rabbit stuck its head slowly and curiously out of the hat and then retreated quickly back inside. It was a bit like a jack in the box. Come to think of it, I didn’t see any jack in the boxes (jacks in the box?). Maybe that’s an American thing.

One of the greatest qualities of this tour guide was how excited he was to hear and play for us every song that the machines played. It’s an admirable quality to still be so amused at something one sees and hears repeatedly every day on the job. It made me think about how I could better appreciate some everyday sights like the scenery on my commute. At the moment in my memory, it seems quite mundane and unsightly, but maybe (probably) there is something nice that I’m missing.

The tour guide talked about how at a certain point in history, people started making outdoor music boxes in the form of barrel organs and street organs in order to democratize the experience of listening to them. The large street organs, he said, are particularly Dutch because in the Netherlands, it was easy to move such beasts along flat ground. In other places, people had to carry the apparatuses on their backs. He had the visitors take turns playing a street organ on display. We were instructed to keep turning the wheel continuously through the handoffs from one person to another – otherwise, it would sound awful and be not-so-great for the machine. The encoded song fed through on a “music book” that folded in a zig-zag pattern. The wheel was quite heavy to turn and required a full-body motion.

It turns out I saw one of these street organs in Delft, though that one was pulled by a horse and hooked up to a motor to play. A couple of guys walked around into the crowd and shook their cans full of change in front of passers-by. The organ played some songs that sounded quite funny when rendered in street organ form. This included “Bye Bye, Blackbird” and a few contemporary pop songs. The same street organ guys (with the same songs) came back to the street market a few times. I found them quite amusing the first time I saw them and somewhat annoying the second and third times (kind of like Waterfire in Providence).

Another interesting bit about the music books was that they made it quite easy to swap out the tune. This contrasted with earlier designs in which the tune was built into the music box and not meant to be changed. I immediately compared this to web programming. These music books were the data, and the music boxes or street organs were the rendering engines (or more generally, the browsers). Some later steel comb type music boxes had their music encoded on cone-shaped perforated steel. This made it easy to nest various tunes inside one another and store them alongside the music box. Steel combs tended to be all different shapes and sizes, which of course required particularly sized tunes. I wondered, with the music books, if there was standardization among different manufacturers of street organs so that the books could be played universally by any street organ. Then, of course, I thought of web standards. It must have been quite magical to encode a song in a music book and then hear it played back in the glory of a street organ.

The most technically impressive instrument I saw was a contraption with a piano and also three violins that all played together. The violins were arranged in an arc, and a circular bow rotated around them. When a particular violin was supposed to play, the machine pushed it forward and activated keys that pressed down on the fingerboard in the right places. There was even a mechanism that oscillated somehow for vibrato (I think it moved the entire violin to do this), though that vibrato sounded quite mechanical since it was at an even tempo. The vibrato was supposed to make the music sound more human, but it failed in my opinion. Also, speaking generally about all the music machines I heard there, none of them had any variation in dynamics (volume); there was a way to vary tempo with the hand-cranked street organs, but I’m not sure if the players ever really used that intentionally; there was no change in timbre; articulation was always uniform; pitch was always perfect (no bending between notes and no adjusting for different chords). A mostly lousy, but in this case, insightful music instructor of mine had an adage that sheet music could only encode about 50% of what was actually expressed when playing music. These music books encoded even less than that, but they were somehow charming in their innocence, like a Pokémon that only knows how to say its name but can’t say any other words.

The tour guide took us into a side room with very tall ceilings. This room housed a few huge organs that were meant for a stage. I’m not sure what they were called. They stood to just a few centimeters below the ceiling, and I was a bit curious about how the museum managed this ship-in-a-bottle situation of getting these monsters into the room. The tour guide explained that in the 1920s, jazz was becoming popular in Europe. Many people in clubs were starting to demand it, but not many musicians knew how to play it, so at the time, jazz musicians were quite expensive. The solution for the club owners was to buy one of these huge and ornate organs – clearly an investment that would take a while to make up for its cost. The company that made these organs in the collection was quite prolific – I believe they produced an organ every two weeks! Our tour guide said he would play something appropriate for the time in order to demonstrate the organ. Also, he pointed out the very nice wood floor in the room that would be suitable in case anyone wanted to dance! He disappeared between the small crevice between the wall and the back of the organ, and he emerged to a spirited rendition of The Charleston. He began shuffling his feet a bit. The visitors clapped at the end of the song.

The tour wrapped up at 16:30, and I had exactly 30 minutes to explore as much of the museum as I could before closing time. I was most curious about how the mechanisms worked, and I found a room that demonstrated exactly what I was looking for – bare pipes and bellows that visitors could operate with a hand crank. They had something like this for every main type of music machine.

As I often did, I found myself not wanting to leave at closing time. If I lived anywhere near Utrecht, I would seriously look into finding a way to be involved with this place. According to their Wikipedia article, their restoration workshops are industry-leading and “known for their excellent standards”. This sounds like exactly my jam. In general, I found it quite inspiring how much this museum embraced such a peculiar niche. This unashamed geeking-out was evident in everything from the diversity and quality of the collection to the enthusiastic tour guide who encouraged us to dance. This approach resonated with me at a time in my life when I am starting to be more public about my love of drum and bugle corps.

- I think these guys turned their heads while they whistled a tune.

- Even the grid of lockers contained some music boxes. We saw some other museums in The Netherlands take this approach of extending the exhibits into the locker room.

- Change snail!

A lot of fun Thanks for sharing!